The Age of Taste

How judgment became the scarcest resource in the AI era

There’s this quote by Ira Glass that lives rent free in my head. I think about it at least once a month, especially when I write, and it perfectly encapsulates both the experience of being creative and the pathway to making truly great creative work, especially now.

“Nobody tells this to people who are beginners, I wish someone told me.

All of us who do creative work, we get into it because we have good taste. But there is this gap.

For the first couple years you make stuff, it’s just not that good. It’s trying to be good, it has potential, but it’s not.

But your taste, the thing that got you into the game, is still killer. And your taste is why your work disappoints you.

A lot of people never get past this phase, they quit. Most people I know who do interesting, creative work went through years of this. We know our work doesn’t have this special thing that we want it to have. We all go through this. And if you are just starting out or you are still in this phase, you gotta know it’s normal and the most important thing you can do is do a lot of work.

Put yourself on a deadline so that every week you will finish one story. It is only by going through a volume of work that you will close that gap, and your work will be as good as your ambitions.

And I took longer to figure out how to do this than anyone I’ve ever met. It’s gonna take awhile. It’s normal to take a while.

You’ve just gotta fight your way through.”― Ira Glass

I’ve written about this at length already, but it bears repeating: the internet is changing and the barrier to entry for creating content has dramatically shifted in the last 24 months. AI-generated content is often associated with having poor taste, due in part to the lack of effort required to generate it.

This is obvious for anyone using social media, but we’ve seen a dramatic rise in the amount of slop content since the release of Sora 2 back in late September, 2025. Endless Facebook posts with AI-generated images was one thing, but by early October of 2025 platforms like Instagram were saturated with video-diffused content.

If you used Instagram or TikTok during this period of time, I’m sure you noticed. But the AI video content most likely found its way into your feed, and it wasn’t because the content was bad. Far from it.

It’s because the content is good enough to trend. This distinction matters. It’s good enough to get reshared, watched, and commented on. And since the release of Sora 2, other platforms like Kling have expanded upon this trend, allowing for increasingly impressive and at times genuinely hilarious content to be produced.

We’re standing at the edge of a precipice, and a few things are clearly true:

The generative capabilities of AI are the worst they will ever be

The cost of these capabilities will decrease, and accessibility will increase

The technical capability required to produce anything you see on a screen is decreasing

Because computers mediate design, nearly everything we touch, buy, or watch can be shaped by AI

Our human brains are static, and we’re working with what we’ve got

Taste, and curating the ingestion of content, is now shifting from being a luxury or an intellectual exercise to being an absolute necessity for sanity in the age of AI. Taste may be the determining factor between making the time for critically acclaimed cinema vs being too brainrotted to even sit through an episode of a serialized Netflix show. If you are what you eat, consuming a rich diet of shorts on platforms like ReelShort may permanently turn your brain into processed jelly.

This trend has become clear, but recent models like Opus 4.5 have made this even more obvious: soon, if you can conceptualize something, you can create it. This is the collapse of technical scarcity, and with it, we have an associated filtering crisis.

The Collapse of Technical Scarcity

This isn’t just a media problem. It’s already reshaping work.

The job market has had its fair share of ebbs and flows over the last two decades, from the housing market collapse through the last few election cycles. But the job market throughout 2025 and early 2026 has felt distinctly different. People are evaluating AI’s capacity to replace people, and there’s a fundamental shift happening with how we’ve traditionally thought of the career ladder when it comes to white-collar work. New college grads cannot find jobs in many fields, period. Reddit’s r/jobs sub is a sobering insight into the realities of what is happening. Hiring recent college grads is way, way down. Why?

When this started happening in late 2024 and early 2025, many people chalked it up to being a result of tariff scares and a correction to previous overhiring. But, looming in the background, was the incredibly obvious answer that was difficult to accept: AI. We were already at a point where multimodal models could put together impressive research reports, and employees already in positions were being highly encouraged (or forced) to use generative AI as much as possible.

Join, or die.

Dario Amodei, CEO of Anthropic, predicts that half of entry-level white collar jobs could be gone within the next 5 years. The speed of this transition will overwhelm our ability to adapt.

What was clear: more (or the same) could be done with less. This trend has continued into 2026, and will only accelerate.

Here’s the reality of 2026 at-a-glance:

Front-end development has been functionally automated overnight

Claude Opus 4.5 can ingest and output more usable, high-quality content than any intern you could possibly hire

At worst, producing realistic photographs, graphics, and videos that used to take days or weeks to produce with a team of people can be done in minutes

The key here that people often misunderstand is this: the generation of software, images, videos, and content in general doesn’t have to be perfect to impact society, it just has to be good enough. And, if we’re being honest, we’re already there.

By the year 2030, we’ll look back on the frontier models (like Opus 4.5) that we’re using now and wonder how we even tolerated them. They’ll look cumbersome, slow, expensive, and poorly optimized. We’ll have much more refined, local models running on our laptops and phones that will run circles around these older models. And, frontier models will be fully agentic, capable of utilizing VMs and using a computer like you.

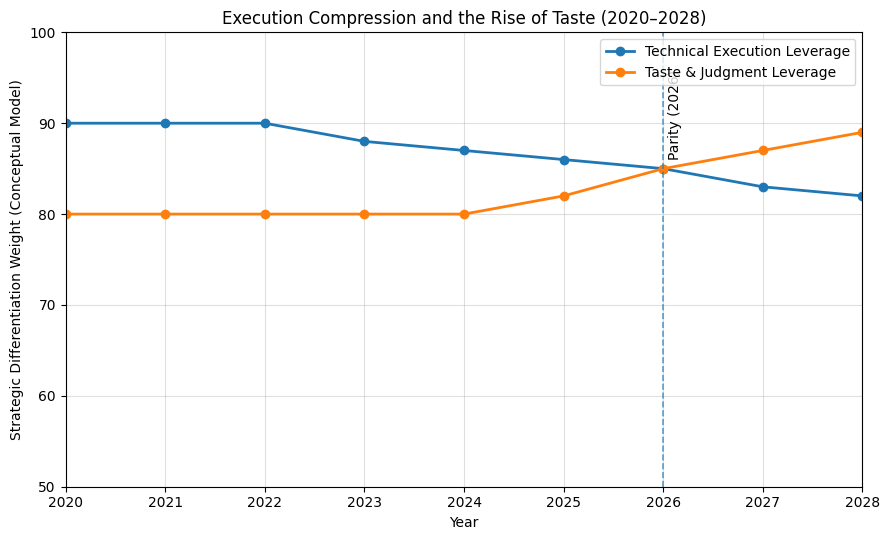

Where does this leave us? If the cost of technical expertise and execution goes down, and accessibility of these platforms goes up, what happens?

The result is an absolute deluge of content and software programs. SaaS will be disrupted, and the cost of subscriptions will decrease as the sheer amount of seemingly identical competition increases. Plenty of technical jobs will still exist, but entry into some fields will become increasingly difficult, and the bar for technical expertise required to truly make an impact as a human will rise considerably.

Shifting through the ocean of content and software will become its own skill, and that’s where taste comes in. In a world where anything can be created if it can be conceptualized, taste will reign supreme.

Compute and software can be bought. Taste is earned.

Defining Taste

I have a friend named Sarah who has impeccable art and design taste. I know that if I ask for a recommendation (be it visual, music, etc) I’m sure to get a good list from her. I also know that her keen sense of taste boils down to a few factors:

She was naturally inclined towards the visual arts, and arts in general, from an early age

She leaned into this natural inclination, and spent countless hours consuming, learning, and honing her skills both as an artist and as a thinker

Her refined sense of taste is a combination of inputs (what she spends her time thinking about) and her outputs (what art she puts out into the world)

Taste compounds.

The point is, this mental curation didn’t happen overnight. Oftentimes it grows over a lifetime, and is informed just as much by what you love as what you dislike.

To be more clear, taste is not:

A vibe

Following trends

Aesthetic snobbery

Taste is a combination of pattern recognition over time, a sensitivity to quality differences, awareness of context, and saying ‘no’ to lots of inputs and outputs. It’s a mental discipline. It becomes a filter against noise and a form of mental hygiene.

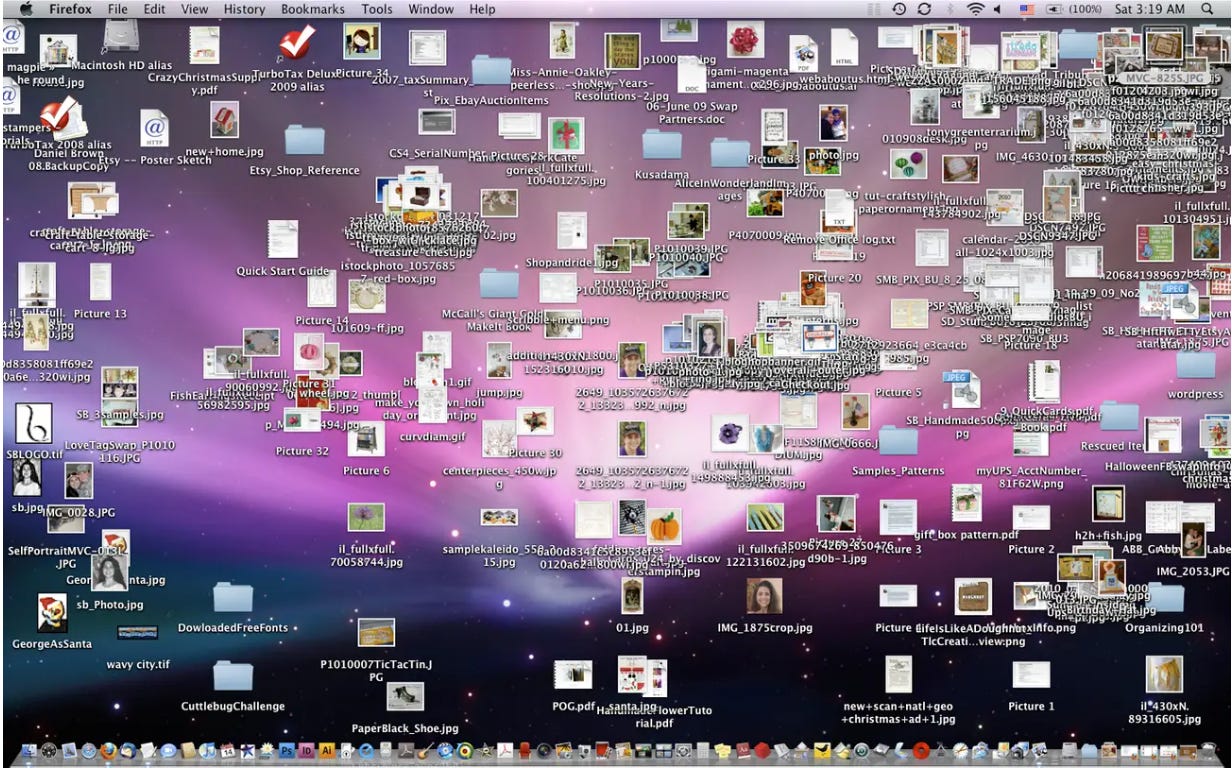

Our digital environments become a mirror of ourselves. How clean is your desktop? How organized are you digitally? Do you walk away from the computer with a sense of relief, or overwhelm?

One of my predictions this year in my last piece was the push towards a renewed analog renaissance. Part of cultivating a sustainable digital diet is knowing what to say no to, and deciding when and what to consume mentally. This was a huge problem as social media got more popular, and it is even more relevant now with the rise of generative AI. Much like with taste, some people have a more natural ability to moderate, and others do not. As the saying goes, if something is free, you are the product.

AI and Taste

Can AI have taste? AI outputs often impress me, but they still leave me feeling cold.

Ben Affleck went viral for his take on utilizing generative AI for writing. His take was the following:

AI writing is shitty because it goes to the mean, to the average

It’s a useful tool if you’re a writer, for ideation and brainstorming

It is incapable of writing genuinely creative, original content

By no means are these revelatory takes, but I generally agree with Ben. While models are rapidly improving, and baseline performance increases monthly, there’s a nuance with taste. AI can approximate taste, and it can create a believable facsimile of it. But, it currently cannot care about taste the same way people do. It can describe the feeling of a painting, but it cannot feel the feelings.

Above is Picasso’s famous painting Guernica. When I see this painting, it evokes feelings of dread, terror, sadness, and the brutalities of war.

If you ask Gemini to analyze this painting, it prefaces its response by reminding you that it doesn’t experience emotions. It clinically and specifically describes the painting in detail, and does so in a way that might make me think it is an art historian. Its description of how things come across sounds accurate, and upon reading its outputs a few times over, I largely agree with its response. But the response isn’t borne from feeling first, and that’s the difference.

As models evolve, and signs of introspection become emergent properties of their presence, this landscape will change.

Taste as Labor

David Shapiro coined this term ‘KVM jobs’ last year, and I find myself constantly coming back to it to accurately describe where we’re heading. KVM stands for keyboard, video, mouse, and KVM jobs essentially means anything done on a computer with your hands and eyes.

KVM-based jobs are eroding, and this isn’t limited strictly to technical domains. More and more of the current work being done will be automatable soon, and what remains is beginning to skew towards judgment. Taste plays an enormous factor here.

Instead of writing code manually, many software engineers are already becoming orchestration leads. Their roles have shifted. Their time is being spent differently, now curation, review, and revision are the name of the game.

This isn’t an isolated phenomenon. This behavior and workflow is bleeding into every other role. To be successful, everyone has to become a project manager. Having a holistic view of a project or body of work is a must. It isn’t enough to just be good at one thing, diversification is essential.

Games are a good example of the results of editing and taste. Games are inherently multidisciplinary, and are experienced as a full-bodied thing. The feeling of playing the latest Mario game is often one of joy, and this feeling is the result of a ton of work, thought, and curation.

To make a great game:

The basic actions must feel good to do over and over

There’s a sense of progression, unlocking, growing, and evolving

The goal for what you’re doing is clear, and you know what you’re working towards

The art and design behind the game is aesthetically pleasing and cohesive (the music, art, and code all work in harmony together)

There’s a balance between novelty, rest, and tension

Much like maturing and growing as individuals, our taste evolves over time. I’m sure you don’t have exactly the same music taste as you did from 10 years ago, that’s a good thing! The refinement of our taste is a never-quite-completed thing, like an endless mind-map, latching onto the next thing the moment we’ve grown comfortable.

We’ve already seen many new job titles come into the mix, but I predict that within the next couple of years we’ll see more titles like:

AI output curator

Orchestration lead

Evaluation lead

Product editor

Embracing the Age of Taste

Some people truly see things before others do. Rick Rubin is one of those people. Last year, Rubin’s site, The Way of Code, went viral. And yes, it’s a playful site based on Lao Tzu. The site and its graphics were vibecoded using Claude, and the site in my opinion is a great distillation of the time and place we’re currently in. Much like a great book, the site is a balance of thought, form, and zen.

I often sit with Rick’s quote on taste: “I know what I like and what I don’t like. And I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like”.

We’ve entered the age of taste, and our collective responsibility for how we want humanity to look is more important than ever.

I’ll leave you with an excerpt from The Way of Code:

People say Source is so grand

it’s impossible to grasp.

It is just this grandness

that makes it unlike anything else.I have three great treasures to share:

Simplicity

Patience

HumilitySimple in action and in thought,

you return to the origin of being.

Patient with both friends and enemies,

you accord with the way things are.

Humble in word and deed,

you inhabit the oneness of the cosmos.

Couldn't agree more, the insight that our own 'killer taste' is precisely what fuels initial disappointment in our creative endeavors is profoundly accurate. This concept, particularly the emphasis on generating a 'volume of work' to bridge that skill gap, is highly applicable to iterative development cycles in computer science and the continuos learning process required for mastery in any complex field, from pedagogy to AI research.

Brillian framing of taste as the new scarcity. The KVM shift is already reshaping teams where junior roles that built foundational skils are vanishing. Interesting how taste isn't just curation but knowing when to break rules, something pattern-matching AI struggles with when trainedon consensus.