Generation Brainrot

GenAI + Attention Algorithms = The Infinite Dopamine Machine

As a kid growing up in the ‘90s, I was obsessed with the cartoon show Gargoyles. I’d rush home from elementary school, plop myself in front of the TV, and sit with full attention for 30 minutes at approximately 4:00 PM every weekday. The show was known for having a darker tone, and I recall enjoying the action and dialogue (and most of all the associated action figures I collected).

We had a rule in our house: I’d watch my show for a half-hour, and then I’d do my schoolwork. Like many kids, I didn’t like doing homework, but I knew the sooner I’d finish the sooner I could do something I really wanted to do. Our family had friends that didn’t allow their children to watch TV or use the computer at all, and I found that odd considering how significant media and computer use was within my family at the time (circa 1999). I owned a Sega Genesis, a Game Boy, and I have fond memories of Rollercoaster Tycoon on the family computer. This was normal.

Sure, we had limits, but even then it was difficult to fathom coming home and just doing homework and reading books. If I spent time at their houses after school, we’d typically play outside, because there wasn’t anything to do inside that was stimulating or entertaining. Different, but totally fine. As kids, playing and using our imagination came so naturally that the act of doing it was never a conscious thought. Video games and media were icing on the cake, but they weren’t the entire cake.

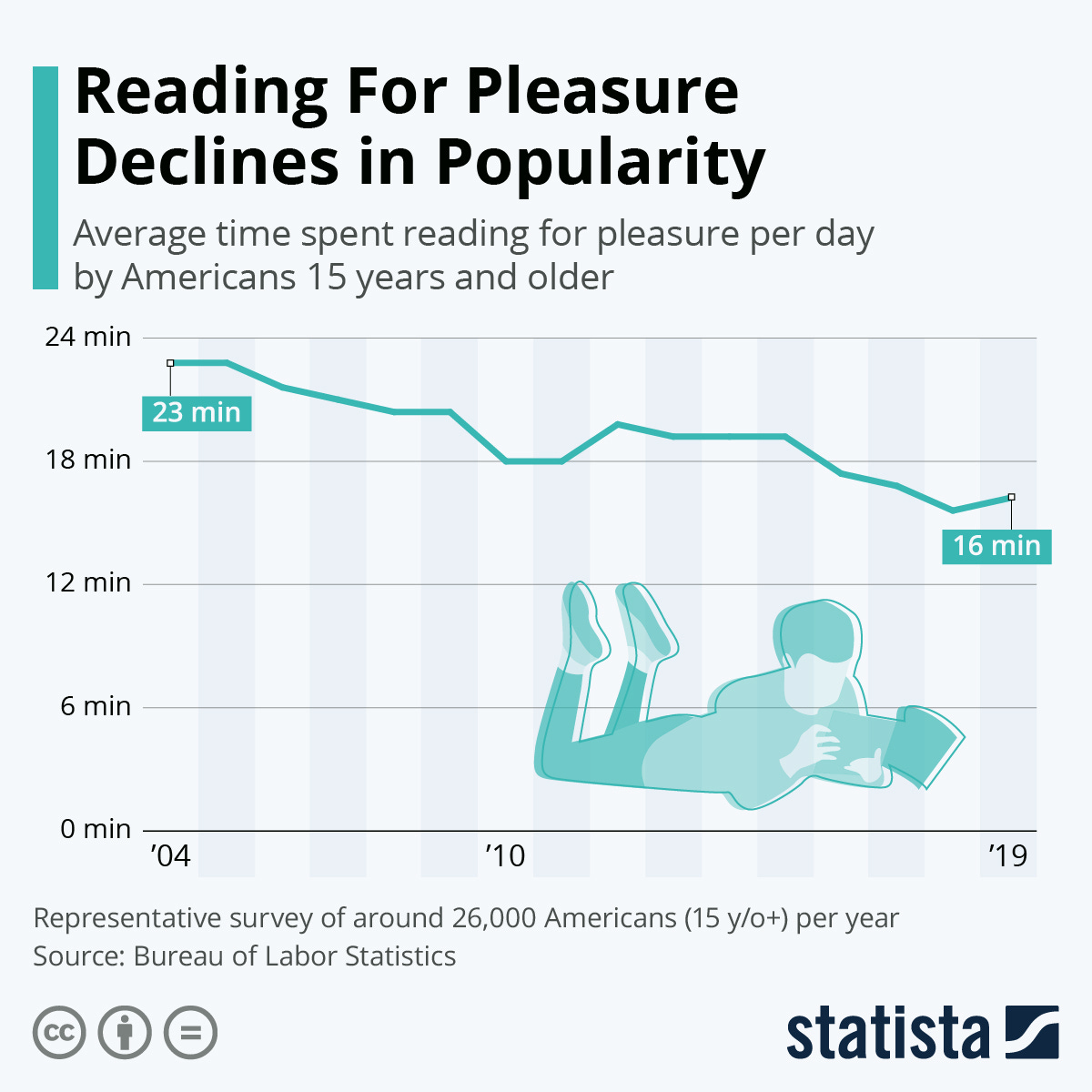

A great deal has changed with media consumption in the last decade. Things that formerly would have been considered unfathomable or bizarre to consume have become the norm, and society has entered an era where the dopamine feedback loops are producing active cognitive harm. Ironically, writing about this phenomenon and social change in depth can be challenging to communicate, because the people that would most benefit from reading this have been rewired to the point where long-form content is actively unenjoyable.

This shift in our ability to pay attention has profoundly impacted how we communicate with each other, enjoy life, learn, and make sense of the world. Increasingly sophisticated social media algorithms have reshaped the world, and generative AI has become the next major unlock for seemingly unlimited content creation. Worst of all, we have not yet taken substantive measures to protect the most vulnerable in our population from the negatives of this technology: our children. The long-term implications of growing up on 4-8 second clips of algorithmically optimized generative AI content are playing out in real time.

In this article, we’ll explore some of the recent takeaways from “Your Brain on ChatGPT” (MIT, 2025), and see how the deadly combination of optimized social media feed algorithms + GenAI has the capacity to cripple many of the traits and features we value most about being human. Much like the brilliant algorithms that are ruining people’s lives, the trajectory of the negative traits of this technology are both predictable and avoidable. You’d think we wouldn’t need doctors to tell us this is impacting our brains in a negative fashion, but common sense isn’t common.

Italian Brainrot: Culture’s Final Form

brainrot [noun]

/ˈbrānˌrät/

A colloquial term describing the cognitive dulling, shortened attention span, and reduced critical thinking associated with prolonged exposure to overstimulating digital content, especially algorithmically-curated media.

I’ll be the first to admit, the first time I saw Tralalero Tralala (a three-legged shark in Nike sneakers) I was amused. There was seemingly no context, aside from the fact that Tralalero fits neatly into a category of GenAI memes that emerged this year called Italian brainrot. Italian brainrot is essentially just GenAI videos and images paired with nonsensical Italian-esque babble. Often, the audio accompanying the videos is completely gibberish. This is a mixture of being somewhat humorous and disturbing. These are the kinds of videos you might send to your odd group chat on Signal with zero context.

I highly recommend the reader take a moment and read the Wikipedia entry for Italian brainrot. Or, if you want to be exposed even more, watch a couple of these videos. Keep in mind, these are longer videos on YouTube that are not cut for TikTok and shorter content consumption.

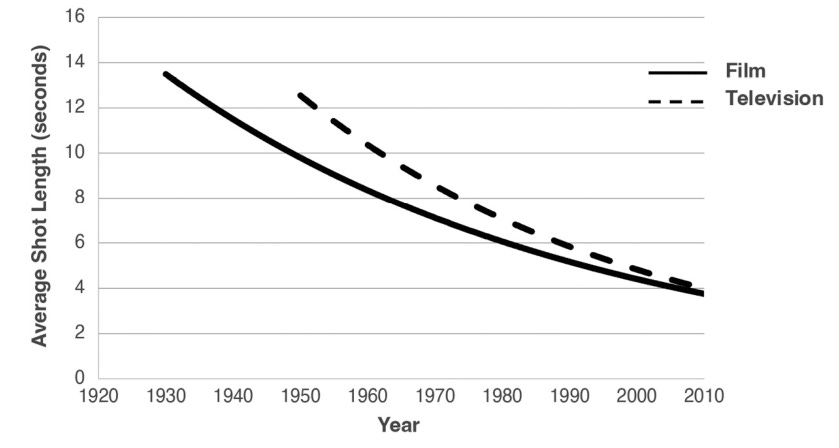

It can be difficult to gauge (or accept) where we go from here. Obviously content and its consumption has gotten shorter and more viscerally nuts as time has gone on. Reels was only launched by Instagram in 2020. Gen Alpha viewers would much prefer a stream of similar GenAI content than be forced to sit down and watch the 1942 cinematic masterpiece Casablanca. But, if we’re honest with ourselves, we know deep down that many of the people we are closest to in our lives today would struggle to sit through Casablanca without constant phone usage (or refusing to watch it at all). Even the pacing of 90’s films feels like a snail’s pace in comparison to films being produced today.

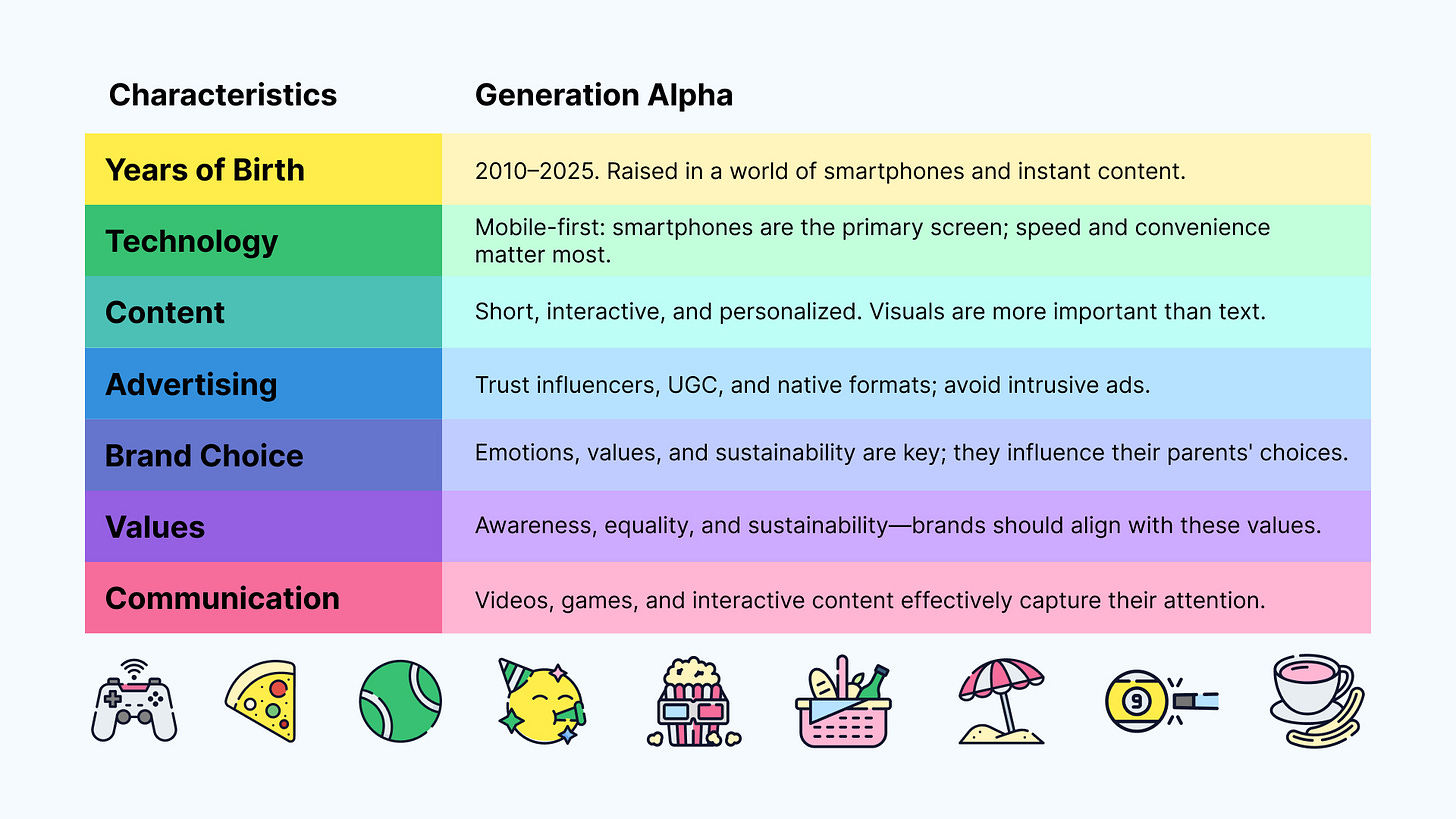

It wasn’t that long ago that the media constantly portrayed Gen Z as being a generation of low attention span, unmotivated dopamine addicted weirdos. Gen Z hyperpop and artists like Billie Eilish were considered somewhat jarring in contrast to the sensibilities of millennials back in 2019. Shrinking attention spans and studies are proving what has long been anecdotal: Gen Alpha has drastically shorter attention spans than Gen Z. Gen Z’s sensibilities and attention spans are feeling normal by comparison.

There are a multitude of compounding factors that lead to shortening attention spans, but media consumption is the primary reason. Each year results in increasingly hyper-stimulated digital environments, better algorithmic design, faster multi-tasking and media switching, and more cunning dopamine hijacking and reward conditioning. It comes as no surprise that attention disorders (and diagnoses for ADHD) have risen in lock-step with modern forms of media consumption.

Data analytics has sped up the dopamine loop. Because we know the moment attention drops off, marketing and editing can be dialed in to capture the most attention possible, according to the data. Like survival of the fittest, the best content on the internet is the content most optimized for the algorithms upon which the content lives. This is totally expected, and the system is working exactly like how it was designed to work. Every second matters. If they’re not watching your video, they’re watching somebody else’s. Content creators have to optimize their content, otherwise monetization becomes practically impossible. The flywheel was already speeding up every year, and then generative AI got good enough to be incorporated into the process. The inevitable result? Italian brainrot.

This is Your Brain on AI

The deleterious aspects of social media consumption and usage have been so widely reported and discussed that you’d be hard-pressed to find someone in America that isn’t aware of the state of play. Much like a teen hooked to their fruit-flavored vaporizer, you can still be acutely aware of the negative aspects of something while being paralyzingly incapable of stopping. This is addiction in a nutshell. Even knowing it is negatively rewiring our brains for rewards and fundamentally reshaping our relationships with others isn’t enough.

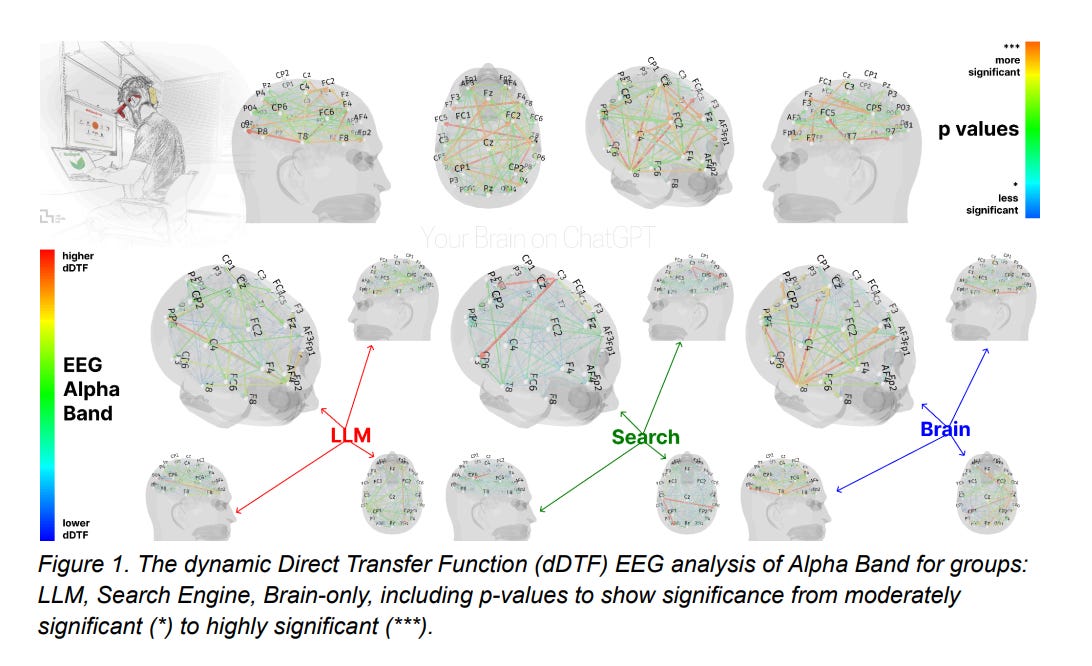

This week, an MIT paper went viral, entitled “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task”. The study confirmed what we all feared: using AI during critical periods of thinking through work (in this case writing) results in lower memory integration, diminished comprehension, and ultimately shallow critical engagement.

The study included college-educated adults between the ages of 18-39 in Boston, assigned to three groups:

Group A: Used ChatGPT to write SAT-style essays.

Group B: Used Google search.

Group C: Brain-only.

The participants wrote 3 essays over this period, with a fourth crossover section to test tool switching. ChatGPT-exclusive users showed “significantly lower neural connectivity”, with the information only superficially passing through the person’s brain. These users couldn’t accurately recall or quote their own work (not a surprise) and this barely differed among the sessions. While ChatGPT reduced mental effort in the short term, it resulted in drastically diminished comprehension, homogeneity when it came to how they actually wrote, and shallow engagement. The Google search and brain-only groups did not experience these deficits, because they had to use their brains to actually write the essays.

It doesn’t come as a shock that LLM-produced essays were often perceived as soulless, lacking originality and personal perspective. English teachers reviewing them noted that “they felt soulless, technically perfect, but devoid of meaning.” The participants that used AI felt a decreased sense of authorship and ownership over their essays, which is more aligned with how someone might feel if they outright plagiarized or cheated. Perhaps most disturbing of all, when the AI users finally switched and were forced to write without AI, they often defaulted to AI-sounding vocab, suggesting that exposure to LLMs changed how they express themselves linguistically.

To contrast this, many of the cons of LLM usage go away if you use them as a tool for proofreading or after an initial edit. The key here is, you’re using AI after you’ve already thought through how you’re thinking about something. Writing is an act. Writing is an active process, so when you cut right to the end you miss out on all the steps along the way. It’s the journey, not the destination.

Education and AI

As society collectively gets lazier as a result of the usage of technology en-masse, there are still certain things we cannot skimp on. I’m sure you can see where I’m going with this. We cannot liberally apply GenAI to every facet of education, particularly with younger children. Studies, like the ones done at MIT, showcase disastrous results when people liberally cognitively offload tasks to AI. It comes as no surprise that doing this creates an over-reliance on AI, eroding self-regulation and inhibiting deeper learning. We’re already seeing this as a regular joke online: the second ChatGPT goes down, everyone jokes on X that their ‘Productivity has dropped to zero!’ This is humorous if you’re in your mid-30s working a job you hate, but a nightmare if you’re 6 years old and cannot keep your attention long enough to learn how to write.

This technology isn’t going anywhere. LLMs running locally in a couple of years will easily rival what OpenAI is offering via the cloud today, and it won’t be long before even better fine-tuned small models run effortlessly (and privately) on your phone. Cognitive offloading using the latest AI models + using that same technology to produce irresistible content = a society of people with low attention spans and the inability to think and act independently. A thousand miles wide and an inch deep.

If Italian brainrot had debuted in some form back in the late ‘90s, it likely would have been met with a huge uproar of public criticism. The idea of children sharing absurdist gibberish videos that are devoid of any sort of meaning certainly would have resulted in a lot of emergency parent-teacher meetings. Today, parents are often even more glued to technology than their children are, and it is ultimately up to the family to decide what devices are used when the day ends.

Generation Brainrot is this: Gen Alpha and Gen Beta are being born into a world where simulacrums of meaning can be generated by artificial intelligence, and further pushed by algorithms meant to capture attention. By the time these generations reach adulthood, this technology will have profoundly shaped the direction of humanity, and any mindless exposure to the negative aspects of this technology will already have done its damage.

The Near Future

Social media is here to stay. We live in the attention economy, and that isn’t changing. Adults have the right to decide how to spend their time, even if they choose to waste it. Our children are a different story. Children do not know any different, and Gen Alpha has already been impacted in a major way by being social media natives and the youngest generation to ever experience and consume generative AI.

We have an incredible opportunity. We can regulate the usage of AI in classrooms, and encourage its use when it is truly collaborative and to the cognitive benefit of the individual. Cognitive offloading using AI before the age of 18 is completely unnecessary; the entire point of school is to learn how to learn, and it isn’t supposed to be easy. However, I’m confident that tools can be developed that take the best of LLMs and refactor them as guides and tutors, instructing students on how to approach problems without outright giving them the answer. AI is a double-edged sword if there ever was one.

Finally, every child in the world has the opportunity to have access to a tutor that, if used reasonably, can contribute positively to human flourishing and potential. That doesn’t mean suggesting AI slop to consume, or assisting with writing essays that sound bland and generic. It means doing what tutors do: meeting someone where they’re at, and helping to guide them. These systems will continue to evolve, and they are as genuinely impressive as they are terrifying in both the scope of their abilities.

Some things you can’t unsee. I’ll never forget the three-legged shark in Nikes named Tralalero Tralala… but that’s the price of admission online. Still, the algorithm doesn’t get the final word. We have the power to reshape how we consume, create, and educate. We can make books cool again. Curiosity doesn’t have to rot. We just have to put the phone down long enough to remember what it means to really think.